It’s Not Just Another Brick in the Wall – Pt. 4

Today, on the site of the once fabled palapa, rests one of three county lifeguard towers whose lifeguards patrol the sand and ocean at Malibu Surfrider Beach. After numerous resident complaints of unauthorized and unpermitted “buildings” on the beach, the County of Los Angeles tore down the palm frond-thatched hut, a task that had to be accomplished a number of times as a select group of locals made numerous attempts at rebuilding it. Although the structure itself has since been gone for a number of consecutive years, the area is still referred to by the current sect of locals as the palapa and those who make the trek from the entrance of the wall down to the palapa area no longer have the same power and control as during those prime years throughout the 1990s. This perpetuation of title proved, however, that the reality and language manifested by the likes of Miki Dora were maintained throughout the years. The society of surfers that I grew to know so well, exemplified the postmodernist perspective of social constructionism. The concept surfers had of their socially assembled reality emphasized the constant mass construction of people’s perceptions in dialectical relations with one another. A surfer’s reality was, and is, formed through habits, which in turn, become institutions. These institutions are supported by language conventions, afforded continuing legitimacy by mythology, religion and philosophy, maintained through socialization, and individually internalized by their upbringing.

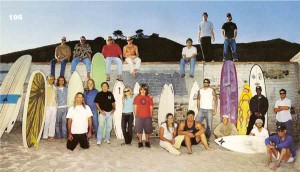

The wall at Malibu has seen a much different fate than that of the short-lived palapa. Memorialized in the minds’ of not just surfers, the wall penetrated the imaginations of millions thanks to the high visibility that was brought on by the millions of people around the worried that witnessed the concrete image on print and in film. Thanks mostly to characters like Miki Dora, the wall has become an icon for surf culture, so much so, that Dora’s own name frequently has been known to appear on the wall almost as a reminder that his spirit lives on. The wall has served as the backdrop for many photos, including the 1964 cover of “Surf Guide,” which donned a smiling Dora. Photographer Leroy Grannis’ took numerous photos of Malibu and the wall, which have been viewed by thousands. The movie “Big Wednesday” hit the big screen in 1978 and was a semi-fictional visual depiction of the events surrounding the society at the Malibu wall nearly two decades prior. Malibu’s infamous wall has also functioned as the basis for an annual surf contest, proclaimed as the “Call To The Wall,” where men and women of all ages compete in the hot July sun. These examples, as well as the continued use of the term palapa to reference an edifice that no longer exists, validate the existence of a nominological occurrence. Nominology states that we get to know things by how we name them [1] and in this case, the entrance to First Point Malibu in the form of a concrete brick wall reinforced the notion that passing through it allowed a person into a world that was comprised of complex systems of acceptance and recognition, spearheaded by individuals who created the rules, mainly for themselves, and who intended on staying at the top of the hierarchy.

The wall at Malibu has seen a much different fate than that of the short-lived palapa. Memorialized in the minds’ of not just surfers, the wall penetrated the imaginations of millions thanks to the high visibility that was brought on by the millions of people around the worried that witnessed the concrete image on print and in film. Thanks mostly to characters like Miki Dora, the wall has become an icon for surf culture, so much so, that Dora’s own name frequently has been known to appear on the wall almost as a reminder that his spirit lives on. The wall has served as the backdrop for many photos, including the 1964 cover of “Surf Guide,” which donned a smiling Dora. Photographer Leroy Grannis’ took numerous photos of Malibu and the wall, which have been viewed by thousands. The movie “Big Wednesday” hit the big screen in 1978 and was a semi-fictional visual depiction of the events surrounding the society at the Malibu wall nearly two decades prior. Malibu’s infamous wall has also functioned as the basis for an annual surf contest, proclaimed as the “Call To The Wall,” where men and women of all ages compete in the hot July sun. These examples, as well as the continued use of the term palapa to reference an edifice that no longer exists, validate the existence of a nominological occurrence. Nominology states that we get to know things by how we name them [1] and in this case, the entrance to First Point Malibu in the form of a concrete brick wall reinforced the notion that passing through it allowed a person into a world that was comprised of complex systems of acceptance and recognition, spearheaded by individuals who created the rules, mainly for themselves, and who intended on staying at the top of the hierarchy.

The patrician Rindge family of the secluded Rancho Malibu battled to keep their expansive, pristine estate exclusively to themselves. When the highway was forced in and the influx of Hollywood royalty followed with it, the very private life, away from publicity on her isolated ranch by the sea, ended up selling her land to the very people whose presence and lifestyles were to make Malibu famous throughout the world. Later the surf-crazed culture made Malibu Beach the progressive epicenter for the sport.” The high profile Malibu commenced with continued into later generations, most significantly catalyzed by the popularity of Gidget during the 1960s. The wall that the protective May Rindge constructed years prior in an attempt to hold on to her last bit of ownership, became a fundamental icon for an entire collection of motivated surfing aficionados, not just in the surrounding community, but all around the world as well. Explained by the theory of the social construction of reality, the phenomenology that occurred through the erection of the wall and the palapa at Malibu epitomized the influence of behavioral geography, as well as the verbal communication and implications produced merely from the wall’s existence. The construction of this wall planted a seed that lead to an exclusive society, rooted from a justly territorial family whose way of life was being threatened. This structure grew into a self-righteous civilization that was dominated by its own policies, laws, and language that eventually materialized into the quintessence of the surfing scene for the entire surfing community. As the wall was positioned at the entrance to the infamous First Point, it became a symbol of initiation and acceptance, a gateway, if you will, into a world where its citizens were living by their own agenda.

The patrician Rindge family of the secluded Rancho Malibu battled to keep their expansive, pristine estate exclusively to themselves. When the highway was forced in and the influx of Hollywood royalty followed with it, the very private life, away from publicity on her isolated ranch by the sea, ended up selling her land to the very people whose presence and lifestyles were to make Malibu famous throughout the world. Later the surf-crazed culture made Malibu Beach the progressive epicenter for the sport.” The high profile Malibu commenced with continued into later generations, most significantly catalyzed by the popularity of Gidget during the 1960s. The wall that the protective May Rindge constructed years prior in an attempt to hold on to her last bit of ownership, became a fundamental icon for an entire collection of motivated surfing aficionados, not just in the surrounding community, but all around the world as well. Explained by the theory of the social construction of reality, the phenomenology that occurred through the erection of the wall and the palapa at Malibu epitomized the influence of behavioral geography, as well as the verbal communication and implications produced merely from the wall’s existence. The construction of this wall planted a seed that lead to an exclusive society, rooted from a justly territorial family whose way of life was being threatened. This structure grew into a self-righteous civilization that was dominated by its own policies, laws, and language that eventually materialized into the quintessence of the surfing scene for the entire surfing community. As the wall was positioned at the entrance to the infamous First Point, it became a symbol of initiation and acceptance, a gateway, if you will, into a world where its citizens were living by their own agenda.

[1] Notes from Comm 443; (CSUCI: Carla Rowland, 2008).