It’s Not Just Another Brick in the Wall – Pt. 2

Surfing at Malibu began somewhere between the 1920s and 1930s and was not generally a problem for the normally territorial woman. “Once they passed the tough and rigorous check-out [armed cowboys at the southern entrance to the ranch], they would head up the Pacific Coast Highway to the recently opened Rancho Malibu. The lads with their boards would crawl through a “friendly” hole in the fence at Malibu Potteries to hit the surf and paddle out to Malibu Point.”[1] In the beginning, Mrs. Rindge’s efforts in keeping the pristine area private resulted in regularly empty beaches and surf lineups. Legendary surfer and surf photographer, Leroy Grannis said, “Before the war, you’d call somebody before you went to Malibu because you didn’t want to surf alone… What we considered to be a crowd, back then, would be a beautiful day, today.” However, “when experienced surfers returned from WWII and went to Malibu, they were alarmed to find their secluded beaches “crowded” by as many as ten surfers at a time. By 1949, “a crowd of surfers” in Malibu meant twenty-five surfers.”[2]

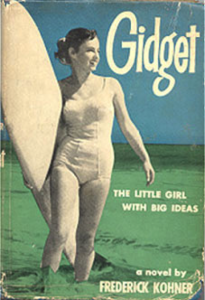

As time progressed and surfing boomed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, especially with the idolization of “Gidget”, whose story arose from her experiences at First Point and at the wall, Malibu was soon considered the “Mecca” of the sport. The influx of new riders and eager spectators created the perfect stage for the regulars, or locals, to demonstrate their superiority both in and out of the ocean. The wall at First Point became a home for these locals, where standouts like Lance Carson, Johnny Fain, and most notably, Miki “Da Cat” Dora ruled the roost and laid the foundation of rules and regulations that would be followed for years after. “Dora’s subtle mastery of wave positioning and the nuances of board control set him apart from the pack at Malibu, and his appearances there became the fodder of legend. His deft mannerisms on and off the beach and calculatedly eccentric comings and goings epitomized the Jack Kerouac/James Dean cult of cool.”[3] Dora had been surfing waves alone at Malibu long before surfing became a fad, which, when the boom of surfing hit, caused him to feel much of the bitter territoriality that May Rindge must have felt when powers larger than herself destroyed her adored land. Contrary to Mrs. Rindge, Miki Dora’s chosen method of retaliation was to impose a strict code of acceptance that revolved solely around the waves and the wall at First Point.

As time progressed and surfing boomed in the late 1950s and early 1960s, especially with the idolization of “Gidget”, whose story arose from her experiences at First Point and at the wall, Malibu was soon considered the “Mecca” of the sport. The influx of new riders and eager spectators created the perfect stage for the regulars, or locals, to demonstrate their superiority both in and out of the ocean. The wall at First Point became a home for these locals, where standouts like Lance Carson, Johnny Fain, and most notably, Miki “Da Cat” Dora ruled the roost and laid the foundation of rules and regulations that would be followed for years after. “Dora’s subtle mastery of wave positioning and the nuances of board control set him apart from the pack at Malibu, and his appearances there became the fodder of legend. His deft mannerisms on and off the beach and calculatedly eccentric comings and goings epitomized the Jack Kerouac/James Dean cult of cool.”[3] Dora had been surfing waves alone at Malibu long before surfing became a fad, which, when the boom of surfing hit, caused him to feel much of the bitter territoriality that May Rindge must have felt when powers larger than herself destroyed her adored land. Contrary to Mrs. Rindge, Miki Dora’s chosen method of retaliation was to impose a strict code of acceptance that revolved solely around the waves and the wall at First Point.

A dynamic hierarchical system based on time and ability was soon the established method of acceptance. At this time, my father, at the young age of thirteen, began surfing First Point and even back in 1962 there was a segregation of surfers that is still witnessed today. He was taught that those who spend the time learning the environment- the waves, the land, the people- will gain respect and earn ‘rights’ to waves and respect in and out of the water. However, showing patience was not the only factor the already recognized locals used to impose their power on others. With the great stylist, Dora, at the head of this newly forming family, the level of ability and style greatly impacted how one was received among the establishment and could determine how successful one was at obtaining waves. Also, hi-jinx and mischief became daily occurrences as Miki and the boys frequently performed pranks and schemes that antagonized, but entertained many on the beach, and most importantly, indicated to all others, who was dominant and in control. Some such antics included giving a grommet an “ostrich”- a whole dug in the sand where a young surfer’s head was placed inside and covered with sand and another involved rubbing soap, as opposed to wax, onto a person’s surfboard. “[Dora’s] most notorious pranks happened in front of the large crowds that gathered at Malibu for contests. In 1965, during the famous duel with Johnny Fain, Dora repeatedly pushed off any shoulder-hoppers, and launched his board at Fain. Then, in 1967 — fed up with the crowds and the “blatant commercialism” of surfing (of which he, too, made profit) – he finished his last wave by dropping his shorts and mooning the judges and crowd of 4,000 onlookers.”[4] Malibu, although often unbeknownst to many, was and still is dictated by a unique pecking order based on the criteria stated above as means to enforce a proper rotation of surfers and waves.

A dynamic hierarchical system based on time and ability was soon the established method of acceptance. At this time, my father, at the young age of thirteen, began surfing First Point and even back in 1962 there was a segregation of surfers that is still witnessed today. He was taught that those who spend the time learning the environment- the waves, the land, the people- will gain respect and earn ‘rights’ to waves and respect in and out of the water. However, showing patience was not the only factor the already recognized locals used to impose their power on others. With the great stylist, Dora, at the head of this newly forming family, the level of ability and style greatly impacted how one was received among the establishment and could determine how successful one was at obtaining waves. Also, hi-jinx and mischief became daily occurrences as Miki and the boys frequently performed pranks and schemes that antagonized, but entertained many on the beach, and most importantly, indicated to all others, who was dominant and in control. Some such antics included giving a grommet an “ostrich”- a whole dug in the sand where a young surfer’s head was placed inside and covered with sand and another involved rubbing soap, as opposed to wax, onto a person’s surfboard. “[Dora’s] most notorious pranks happened in front of the large crowds that gathered at Malibu for contests. In 1965, during the famous duel with Johnny Fain, Dora repeatedly pushed off any shoulder-hoppers, and launched his board at Fain. Then, in 1967 — fed up with the crowds and the “blatant commercialism” of surfing (of which he, too, made profit) – he finished his last wave by dropping his shorts and mooning the judges and crowd of 4,000 onlookers.”[4] Malibu, although often unbeknownst to many, was and still is dictated by a unique pecking order based on the criteria stated above as means to enforce a proper rotation of surfers and waves.

The reality constructed by this socially dynamic and different group of fairly young individuals was not just comprised of a self-imposed set of regulations and policies for proper behavior, but also developed an entirely new and diverse surf-specific language, full of modified and made-up jargon. Words developed at this time and still used today include: kook, snake, and grommet.[5] This language, as pointed out by Professor Clarke, was empowering in that it helped transcend and capture the reality that was occurring at that moment, allowing it to perpetuate into future generations. It allowed this clan of nomadic individuals to feel they were a part of a whole – united as one collective with the interest of this small, barely untouched piece of surf heaven at heart. The language constructed amongst this tight-knit clan of rebel surfers was also limiting because in reality, language is only a symbol, which can be arbitrary, ambiguous, and abstract, and has the potential of falsifying an experience.[6] Although hegemony can often create groupthink [7] each individual member has the potential of perceiving the language in his or her own unique way. For instance, a local may call another local a kook in a playful manor, but depending on the receiver’s connection to the word kook, he or she may respond accordingly or react in the opposite manner than the sender intended. Whether or not the occurrence of a newly created language was positive or negative, it was nonetheless, strong enough to carry on decades into the future.

[1] Chapter six. Thomas W. Doyle, The Story of Malibu. ed. Luanne Pfeifer (Malibu: The Malibu Lagoon Museum, n.d.).

[2] See “Malibu Development: War Years to Late 1940s.” Malibu Complete, History of Malibu. 14 May 2008,12 May 2008 <http://www.malibucomplete.com/mc.history.php>.

[3] Drew Kampion. Miki Dora (1936-2003). October 2000,12 May 2008 <http://www.surfline.com/surfaz/surfa z.cfm?id=792>.

[4] Jaz Kaner, “Malibu – Surfing A to Z,” October 2000, Surfline. 13 May 2008 <http://www.surfline.com/surfaz/surfaz.cftn?id=857>.

[5] “Kook”- (n) a clueless beginner surfer or to any person who is apparently ignorant or lacking basic intelligence. HA! That kook just fell on that wave! “Snake”- (v) To drop in front of someone while they have already caught and are standing on a wave. That kook was in front of me. He shouldn’t have snaked my wave “Grommet”- [n) Generally a surfer under the age of 15. The grommet got a mouth full of sand for talking back to an elder.

[6] Tracylee Clarke, “Social Constructionism,” Notes from COMM 443 (CSUCI, 2008).

[7] Rudolph Verderber, K. Verderber and Cynthia Berryman-Fink. Interact: Interpersonal Communication Concepts. Skills, and Contexts. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

The tale continues… The Wall – Part Three